The Literature

History of Independent Living

by Gina McDonald and Mike Oxford

This account of the history of independent living stems from a philosophy which states that people with disabilities should have the same civil rights, options, and control over choices in their own lives as do people without disabilities.

The history of independent living is closely tied to the civil rights struggles of the 1950s and 1960s among African Americans. Basic issues–disgraceful treatment based on bigotry and erroneous stereotypes in housing, education, transportation, and employment — and the strategies and tactics are very similar. This history and its driving philosophy also have much in common with other political and social movements of the country in the late 1960s and early 1970s. There were at least five movements that influenced the disability rights movement. The first social movement was deinstitutionalization, an attempt to move people, primarily those with developmental disabilities, out of institutions and back into their home communities. This movement was led by providers and parents of people with developmental disabilities and was based on the principle of “normalization” developed by Wolf Wolfensberger, a sociologist from Canada. His theory was that people with developmental disabilities should live in the most “normal” setting possible if they were to expected to behave “normally.” Other changes occurred in nursing homes where young people with many types of disabilities were warehoused for lack of “better” alternatives (Wolfensberger, 1972).

The next movement to influence disability rights was the civil rights movement. Although people with disabilities were not included as a protected class under the Civil Rights Act, it was a reality that people could achieve rights, at least in law, as a class. Watching the courage of Rosa Parks as she defiantly rode in the front of a public bus, people with disabilities realized the immediate challenge of even getting on the bus.

The “self-help” movement, which really began in the 1950s with the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous, came into its own in the 1970s. Many self-help books were published and support groups flourished. Self-help and peer support are recognized as key points in independent living philosophy. According to this tenet, people with similar disabilities are believed to be more likely to assist and to understand each other than individuals who do not share experience with similar disability.

Demedicalization was a movement that began to look at more holistic approaches to health care. There was a move toward “demystification” of the medical community. Thus, another cornerstone of independent living philosophy became the shift away from the authoritarian medical model to a paradigm of individual empowerment and responsibility for defining and meeting one’s own needs.

Consumerism, the last movement to be described here, was one in which consumers began to question product reliability and price. Ralph Nader was the most outspoken advocate for this movement, and his staff and followers came to be known as “Nader’s Raiders.” Perhaps most fundamental to independent living philosophy today is the idea of control by consumers of goods and services over the choices and options available to them.

The independent living paradigm, developed by Gerben DeJong in the late 1970s (DeJong, 1979), proposed a shift from the medical model to the independent living model. As with the movements described above, this theory located problems or “deficiencies” in the society, not the individual. People with disabilities no longer saw themselves as broken or sick, certainly not in need of repair. Issues such as social and attitudinal barriers were the real problems facing people with disabilities. The answers were to be found in changing and “fixing” society, not people with disabilities. Most important, decisions must be made by the individual, not by the medical or rehabilitation professional.

Using these principles, people began to view themselves as powerful and self-directed as opposed to passive victims, objects of charity, cripples, or not whole. Disability began to be seen as a natural, not uncommon, experience in life, not a tragedy.

Wade Blank began his lifelong struggle in civil rights activism with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to Selma, Alabama. It was during this period that he learned about the stark oppression, which occurred against people considered to be outside the “mainstream” of our “civilized” society. By 1971, Wade was working in a nursing facility, Heritage House, trying to improve the quality of life of some of the younger residents. These efforts, including taking some of the residents to a Grateful Dead concert, ultimately failed. Institutional services and living arrangements were at odds with the pursuit of personal liberties and life with dignity.

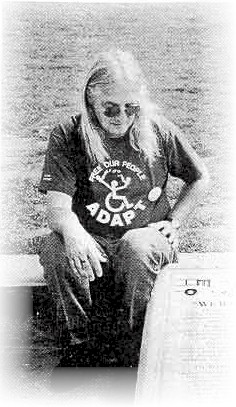

In 1974, Wade founded the Atlantis Community, a model for community-based, consumer-controlled, independent living. The Atlantis Community provided personal assistance services primarily under the control of the consumer within a community setting. The first consumers of the Atlantis Community were some of the young residents “freed” from Heritage House by Wade (after he had been fired). Initially, Wade provided personal assistance services to nine people by himself for no pay so that these individuals could integrate into society and live lives of liberty and dignity. In 1978, Wade and Atlantis realized that access to public transportation was a necessity if people with disabilities were to live independently in the community. This was the year that American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit (ADAPT) was founded.

On July 5-6, 1978, Wade and nineteen disabled activists held a public transit bus “hostage” on the corner of Broadway and Colfax in Denver, Colorado. ADAPT eventually mushroomed into the nation’s first grassroots, disability rights, activist organization.

In the spring of 1990, the Secretary of Transportation, Sam Skinner, finally issued regulations mandating lifts on buses. These regulations implemented a law passed in 1970-the Urban Mass Transit Act-which required lifts on new buses. The transit industry had successfully blocked implementation of this part of the law for twenty years, until ADAPT changed their minds and the minds of the nation. In 1990, after passage of the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA), ADAPT shifted its vision toward a national system of community-based personal assistance services and the end of the apartheid-type system of segregating people with disabilities by imprisoning them in institutions against their will. The acronym ADAPT became “American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today.” The fight for a national policy of attendant services and the end of institutionalization continues to this day.

Wade Blank died on February 15, 1993, while unsuccessfully attempting to rescue his son from drowning in the ocean. Wade and Ed Roberts live on in many hearts and in the continuing struggle for the rights of people with disabilities.

These lives of these two leaders in the disability rights movement, Ed Roberts and Wade Blank, provide poignant examples of the modem history, philosophy, and evolution of independent living in the United States. To complete this rough sketch of the history of independent living, a look must be taken at the various pieces of legislation concerning the rights of people with disabilities, with a particular emphasis on the original “bible” of civil rights for people with disabilities, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973.

References

DeJong, Gerben. “Independent Living: From Social Movement to Analytic Paradigm,” Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 60, October 1979.

Wolfensberger, Wolf The Principle of Normalization in Human Services. Toronto: National Institute on Mental Retardation, 1972.

Important Writings on Independent Living

No Pity- People with Disabilities Forging a New Civil Rights Movement was written by Joseph P. Shapiro in 1993. No_Pity by Shapiro

The Independent Living Service Model – Historical Roots, Core Elements and Current Practice was prepared by Mary Ann Lachat in 1988 and edited again in 2002. This publication traces the IL Movement from concept to implementation in detail. IL Service Model by Lachat

The Independent Living Movement: Its Roots and Origin is a slide presentation prepared by Paul Spooner, Jini Fairley and Stephanie Poitras of the MetroWest Center for Independent Living. Roots and Origins by MWCIL

The Challenge of Middle Age for the Independent Living Movement by Gerben DeJong was written around 1988 – 10 years after the passage of important Amendments to the Rehabilitation Act. These amendments included Title VII which supplied grants to Independent Living Centers. Challenge of Middle Age for IL Movement by DeJong

Consumer Control in Independent Living was prepared in 1988, and examines the principle of Consumer Control and how this principle is actualized in policy and practice. Consumer Control in IL

A Philosophical Foundation for the Independent Living and Disability Rights Movements by Peg Nosek, Yayoi Narita, Yoshiko Dart and Justin Dart was written in 1982 argues that the movement requires a basic shift in society which starts with each individual. Philosophical Foundation for IL and Disability Rights Movement

The Movement for Independent Living: A Brief History by Margaret Shreve was written around 1982. Movement for IL by Shreve

The Independent Living Movement: Where We’ve Been, Where We’re Going is the participants’ manual from a national teleconference and webcast event in 2004. The manual is a collection of important writings about the history, philosophy and implementation of the IL Movement. IL Movement Where We Have Been Where We Are Going

Freedom of Movement – Independent Living History and Philosophy is written by Steve Brown of the Institute of Disability Culture in 2000. Mr. Brown has provided a well-researched history and articulate view of the IL Movement. Freedom of Movement by Brown

Understanding and Accommodating People with Multiple Chemical Sensitivity in Independent Living by Pamela Reed Gibson, PhD. (James Madison University) was published in 2002. Multiple Chemical Sensitivity in IL by Reed

Independent Living and Traditional Paradigms by Gerben DeJong in 1978 is a chart highlighting and clarifying the difference between the traditional medical model and the independent living paradigm. IL and Traditional Pardigms by DeJong

An Evaluation of the Disability Experience by the Life Without Limits Project was written around 2006. This writing shows that while much progress has been made, there is still much to be done. The authors provide some ideas for how to achieve more. State of Disability in America

The Concept of Independent Living – A New Perspective in Rehabilitation by Ingolf Österwitz was written in 1994. This document studies what independent living means. Concept of IL by Osterwitz

A Little History Worth Knowing by Timothy M. Cook is a classic. History Worth Knowing by Cook

Tim Cook, 38, Ex-Civil Rights Aide Who Set Off Storm is a brief biography and obituary written in 1991 by Frank J. Prial. Cook Obituary by Prial

The Reverend Wade Blank, 1940-1993 is a tribute to Wade Blank written by Justin Dart in 1993. Tribute to Wade Blank by Dart

Wade Blank’s Liberated Community by Laura Hershey is abridged from The Ragged Edge shortly after Wade Blank’s death in 1993. Wade Blanks Liberated Community by Hershey